(The following is an excerpt from a 1992 convention lecture given by Marc Silber. It was originally published in “American Lutherie: The Quarterly Journal of the Guild of American Luthiers,” Number 47/ Fall 1996 pp 46-49 by Colin Kaminski.)

I started off in Detroit. Then I started playing music at about twenty when I was at University in Ann Arbor. Before that I could play three songs on the ukulele, but I never thought of myself as a musician. Then the Folk Revival came and soon enough had an old instrument that sounded better than my new Gibson. That was the beginning of me going off the deep end.

By 1960 the Ann Arbor gang was traveling across the country, back and forth, and wound up in Berkeley. The early “folkies” were a beatnik bunch. I was the second one to go from Ann Arbor to Berkeley. I traveled between Michigan and the Bay Area a lot in those days. Within six months, thirty people had arrived from Ann Arbor, a bunch of coffee-drinking, music-playing bohemians.

There was Al Young; he’s a writer now, teaching at Stanford. He’d been out of music for about twenty-five years, but now he’s back into it. He writes literary books.

Then there was Perry Lederman. He was the greatest fingerpicker I ever heard. He died last year. He was the greatest in 1959 and is still the greatest I ever heard. He made one record. He traveled all over the country and astounded people. He was real young, just sixteen when he came to school. We had never seen anything like it. We didn’t even know what fingerpicking was. To me, he was a hundred times better than Chet Atkins. He came from the Village in New York. Perry was the only one in the Ann Arbor Folk Club that knew anything about guitars. He always had a model 0-28 New York Martin. He appreciated it like a classical musician. Perfection, perfect action. In fact, he told me before he died, “Remember when I used to yell at that guy Eugene Clark for not setting up my guitars right? He really did a perfect job, and I was just crazy. That was the best action I ever had.”

One night in 1960 I stopped by a shop window in Berkeley. It said Jon and Deirdre Lundberg Fretted Instruments, and it was full of old instruments. I was there at 6:00AM the next morning and waited until they opened, which was at noon. When I went in I thought I was in wonderland. I’d only seen about twenty old instruments in my life before that.

The Lundbergs were friendly. Jon had folk music posters from everywhere. There were already a hundred posters up from all over the country. Jon Lundberg is a great, weird folk player with a unique 12-string style, and we all learned a lot of tunes from him. They eventually taught me tons of stuff about old American instruments. Little by little I thought, “This looks like an interesting thing. If I found a broken guitar, could I fix it?”

Jon already had what seemed like complete knowledge of the makers, the sizes of instruments, and all the woods. He taught me how to look at an instrument from the outside and guess what the quality was, or if it was something I would like before I bought it.

Jon had a sense for modification. Intonating saddles and cutting Martin bracing back to pre-war standards that was all part of Lundberg’s fearless approach. He would say that you could do this or that to an instrument and then it would be a different thing. This is a repairman’s sense, as opposed to a luthier’s. A luthier would start with nothing and build a new one. But to be able to take a guitar that will not do what you want, and make it do what you want, that is a repairman’s sense.

For instance, there weren’t any 12-strings on the market, so later, at my New York shop I converted many Kays and Harmony Sovereigns to 12-strings. We would extend the peghead and put new veneers front and back. I sold one of those to Happy Traum in 1963. Every time I see him he says “I should never have sold that cheap 12-string.”

When I got back to Michigan I was sending repairs to the Lundbergs via UPS (it was called Railway Express back then) and waiting months, just to get a bridge glued on. By the beginning of 1963 I decided I’d better just venture out to learn to do that kind of thing myself.

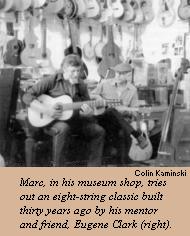

That same year I was working in the back room of the Lundbergs’ shop. Jon called back to me and said that someone had brought in a wonderful guitar and that I should come look at it. It was a classical guitar made by Eugene Clark of Berkeley, California. Eugene has been my mentor ever since. He taught me the guitar from the natural point of view, from the inside out. Glue needs wood, glue expands, hot water expands, wood expands or shrinks. I had not previously thought like that. Most of what I know about how guitars work, maybe all of what I know, is from him.

Through Eugene Clark’s influence I developed a bit of a backward approach. Eugene taught that you’ve got to really understand that string first, the music it’s going to play whatever culture, for whatever pitch, for whatever style, and so on. Then build a box around it. It’s as if you were designing an Indianapolis race car by first considering the available fuel, and building an engine and a car around that. It’s a crude comparison, but you get the idea.

To my way of thinking Eugene Clark is so advanced in all the aspects of what we are trying to do that very few people understand these advances. It is always easier to assign negative aspects to things that are not understood and might compete with what one already knows. Here’s a good example: Eugene made his tools, tempered the metals, and also tunes them. You could tap on each chisel and hear that they were all tuned to the same pitch. Once I asked him if a chisel’s cutting ability was affected by this. I had been using chisels all along, and I was as good at sharpening blades from when I was a canoeing guide as a teenager. My tools were sharp. Eugene asked me to place a regular 2×4 board in the vise and cut through it across the grain with his chisel while holding one hand behind my back! The chisel went silently and effortlessly through the board leaving a perfect channel. It did not tear the wood, but seemed to separate the cells in a nearly silent manner. I was impressed by how much I had to be physically grounded and balanced in order to cut through a board in this manner.

These tools had their wooden handles French polished all those years ago. Eugene says they still look fine, and the finishes have never worn off. For me, that settles a lot of questions as the beauty and durability of French polish.

At the end of 1963 I decided to go to New York. So I thumbed to my folks’ place in Michigan and picked up a bunch of my instruments and my ’52 Studebaker. Then I went to New York and got broke. I went to sell an instrument and realized, much to my surprise, that nobody knew anything, nor did they want to pay anything for instruments I thought were great. I went to complain to someone at the New York Folklore Center named Israel “Izzy” Young, the owner who took instruments on consignment. I said, “These people… and I’m broke… and they won’t…” He said, “Well, if I found someone that knew about that stuff I’d open a shop with them.” Since I had about $4, I thought it was a great idea.